In the summer of 1973, researchers in the Signal and Image Processing Institute at the University of Southern California (USC) were in the process of curating a new set of standard test images for use in for their research. The criteria for one of the remaining images was as simple: it needed to be a scan of a glossy photograph, and the photograph needed to prominently feature a human face. An unnamed graduate student walked into the lab with the latest issue of Playboy magazine, and a portrait of the centerfold, Lena Soderberg, was cropped, scanned, and went on to become the most famous image in the field of image processing.

A brief preamble:

I originally wrote this essay for a photography history class in the winter of 2022 (HIST201 for any other UBC students/alumni out there). I’ve made some minor revisions for clarity and brevity since then, but the content remains largely the same, warts and all. Summer of 2023 is coming to a close as I republish this on my shiny new blog, and the discourse surrounding generative AI art of all kinds has grown more heated than ever. I must say that the themes of identity, consent, and computation throughout this paper have never been more prudent! Anyways, apologies in advance for the drier academic tone in this paper. I hope you find it compelling, or at the very least learn some vaguely interesting fact to tell your friends. -Matthew

A brief preamble:

I originally wrote this essay for a photography history class in the winter of 2022 (HIST201 for any other UBC students/alumni out there). I’ve made some minor revisions for clarity and brevity since then, but the content remains largely the same, warts and all. Summer of 2023 is coming to a close as I republish this on my shiny new blog, and the discourse surrounding generative AI art of all kinds has grown more heated than ever. I must say that the themes of identity, consent, and computation throughout this paper have never been more prudent! Anyways, apologies in advance for the drier academic tone in this paper. I hope you find it compelling, or at the very least learn some vaguely interesting fact to tell your friends. -Matthew

In this essay, I posit that the proliferation of the Lena photo in the 1980s was symptomatic of growing misogyny in the field of computer science. We’ll begin by exploring a brief history of the photograph itself, then contextualize its lifespan within the shifting social demographics of computer science at that time. To conclude, I’ll argue that the photo no longer has any merit as a tool for research, and its continued usage only serves to perpetuate biases.

At the time of its induction into the field of computer research, the Lena image had a variety of qualities which made it desirable as a test image. The aforementioned glossiness of the original magazine print was conducive to a high dynamic range, allowing the initial electronic scan of the image to capture a wider range of brightness and darkness than a photo printed on a rougher medium. The framing of the original full-body shot allowed the researchers to easily make a clean shoulder-crop which placed Lena’s face squarely in the center of the photo, while still capturing a “nice mixture of detail, flat regions, shading, and texture” in its extraneous features, such as the feathers on the hat or the mirror in the background. All in all, the Lena image’s compositional and material qualities made it an ideal candidate for certain research purposes, and the USC Signal and Image Processing Institute included a wide array of other test images (with different qualities and benefits for different use cases) in the release of their test image archive.

By the early 1990s, the Lena image was being published in upwards of 150 research papers per year, being pumped through a myriad of file compression algorithms, facial-recognition processes, and other instruments within the realm of computer research. Its frequency and ubiquity had far surpassed any of its peers from the original test image archive distributed by USC in 1973.

At the same time the Lena image was gaining traction, there was a profound, worldwide shift happening in the demographics of the computer science scene - specifically, a shift from working-class women to upper-middle class men. In 1972, TU Dresden in Germany reported that 80% of its Computer Science students were women. By 1986, there was a near-even 50% split. By 1999, the statistic had fallen to approximately 10%. In 1984, 37% of Computer Science degrees in the United States were awarded to women. By 1994, women accounted for only 28%.

These statistics are not presented to claim that women had become less intelligent, or men more intelligent, or that the field of study had grown too difficult. After all, the early study and industry of computers from the early 1900s to the 1960s had been driven by the hard work and cunning of millions of unrecognized women, and women have continued to be integral at every major step of innovation. In her paper on the subject, University of Maryland professor and computing historian Diane Prost O’Leary instead attributes this gender shift to several self-perpetuating social and historical factors. These factors include the portrayal of male computer technicians in popular media, pre-college opportunities targeted towards boys, existing misogyny within institutions of higher education, and shifting perceptions of female roles within society.

Firstly, does the photograph still have merit as a benchmark test image? While its original positive qualities remain unchanged, the field within which it exists has drastically changed since its inception, in part due to the overuse of the Lena image itself. In their paper, Worn-out images in testing image processing algorithms, Michael Wirth and Denis Nikitenko provide a rigorous analysis of Lena’s place in the research community thirty-eight years after it was introduced. While their paper goes into technical depth far beyond the scope of this essay, their findings all point towards the conclusion that the Lena image has less than no merit as a benchmark image: in fact, its rampant and continuous overuse is detrimental to the integrity of algorithmic research as a whole. Simply put, using the same image to train more and more advanced algorithms over and over again doesn’t improve computers’ ability to process images; it only improves their ability to process the Lena image.

Furthermore, Wirth and Nikitenko discovered widespread misuse of the image. Recall that the Lena image was initially selected for a few distinct qualities - namely its high dynamic range and its human subject. By the early 2000s, the Lena image was being artificially altered and manipulated for research that took no advantage of these original qualities. While repeated use of one ‘benchmark’ image may have been pragmatic during the 1970s when electronic scanners were expensive and scarce, there is no scientific justification for continuous use of one outdated image when modern photographic technology allows for the easy acquisition of relevant, high-quality images.

Secondly, and perhaps most importantly, what does Lena Soderberg think about the usage of her likeness in this way? The problem of consent, reproduction, and distribution is as old as the photograph itself, but the Lena image marked a new precedent for a new, digital age - an age in which photos can be infinitely copied, shared, and viewed across the world. Indeed, the Lena image was one of the first to be uploaded to the ARPANET, a precursor to the modern Internet.

In a 2019 interview, Lena recounted first-hand how her life had unfolded, separate yet parallel to the life of her world-famous, titular photograph. Unsurprisingly, no-one in computer research had ever reached out to her to ask for her consent to use her likeness in the development, training, and testing of countless algorithms and inventions. Despite expressing regret that she was never consulted or compensated for her work, Lena remains graceful in her advanced age -

she is grateful that she was able to help people, however indirectly and unintentionally. However, now informed of the problematic nature of her photo’s continued usage, she has expressed her desire for the image to be retired.

In a 2019 interview, Lena recounted first-hand how her life had unfolded, separate yet parallel to the life of her world-famous, titular photograph. Unsurprisingly, no-one in computer research had ever reached out to her to ask for her consent to use her likeness in the development, training, and testing of countless algorithms and inventions. Despite expressing regret that she was never consulted or compensated for her work, Lena remains graceful in her advanced age -

she is grateful that she was able to help people, however indirectly and unintentionally. However, now informed of the problematic nature of her photo’s continued usage, she has expressed her desire for the image to be retired.

To some extent, this appears to be the end of the Lena photo’s story - in recent years, several academic journals have discouraged or even banned the use of the photograph in papers. Yet the photo’s continued use in spite of these measures stand as a testament to the importance of the Lena photo as an artifact of computing and photographic history, as well as an indicator of continuing misogynistic trends within the field of computer science. Lossy color image compression based on quantization, an image compression paper published by the University of British Columbia, was written in 2015 (just 5 years prior to the writing of this essay) and features prominent use of the Lena image as a ‘benchmark’.

These problematic trends in computer science continue past the realm of image processing; Susan Bennett, the voice actress behind Siri, has never been given official recognition for her work by Apple, and was unaware that her voice had been used in such a manner until 2011. Suzanne Vega’s hit song Tom’s Diner was extensively used in the testing and development of the MP3 music format without her knowledge or consent.

Photographs have extraordinary power as artifacts of history, as well as concrete expressions of humanity. While the Lena image lives on as a historical document, it is emblematic of an inequality and dehumanization that does not do justice to the rich history of computer science, especially with regards the women who were and are instrumental to its development as a scientific field.

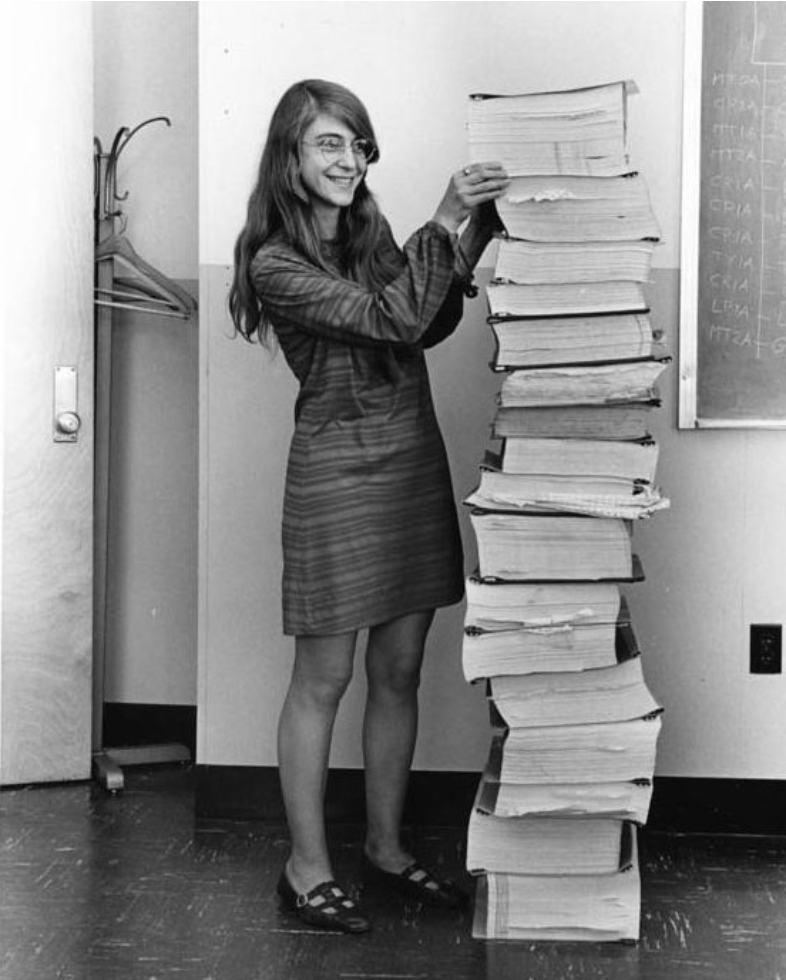

To conclude this essay on a more positive note, I’ll briefly share an often overlooked image from NASA’s Apollo mission photo archives. It’s not a photo of the vast expanses of space, of strong muscular men welding rocket parts, or even the moon. It’s this photo of Margaret Hamilton, head of NASA’s Software Engineering Division:

To me, this photo crystallizes the true spirit of computer programming: a passionate craftsperson, smiling beside a monolith of hard work and ingenuity. The gargantuan stack of papers contains the guidance software for the Apollo mission rockets, painstakingly hand-coded, revised, updated, and tested by Margaret and her team. It’s incredible to know that that unassuming stack of papers was instrumental in humanity’s first forays into the infinite expanses of outer space. Together, I think that the Lena photo and the Margaret photo serve as salient pieces of history that together show how media can indicate and perpetuate inequality, yet also succinctly capture and inspire human triumph in deep and nuanced ways.

To me, this photo crystallizes the true spirit of computer programming: a passionate craftsperson, smiling beside a monolith of hard work and ingenuity. The gargantuan stack of papers contains the guidance software for the Apollo mission rockets, painstakingly hand-coded, revised, updated, and tested by Margaret and her team. It’s incredible to know that that unassuming stack of papers was instrumental in humanity’s first forays into the infinite expanses of outer space. Together, I think that the Lena photo and the Margaret photo serve as salient pieces of history that together show how media can indicate and perpetuate inequality, yet also succinctly capture and inspire human triumph in deep and nuanced ways.